13 May: ‘No assertion of rights,’ say experts about the Abolition of Slavery in Brazil

13 de May de 2025

By Marcela Leiros – From Cenarium

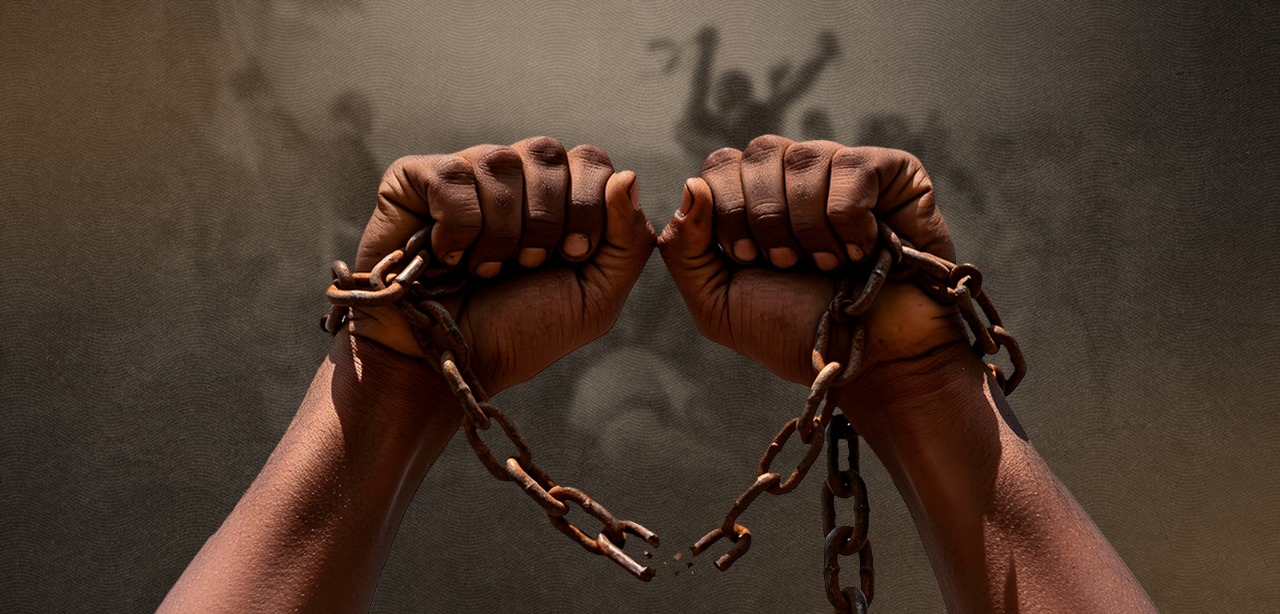

MANAUS (AM) – Although traditionally associated with a humanitarian advance, the Abolition of Slavery in Brazil, on 13 May 1888, did not represent real freedom for Black people, according to experts interviewed by CENARIUM. This is because it took place without guaranteeing basic rights to the Black population, after more than 300 years of slavery.

The abolition in Brazil occurred with the enactment of the Lei Áurea, or Law 3,353, on 13 May 1888, sanctioned by Princess Isabel, which declared slavery abolished throughout Brazilian territory. The country was one of the last in the West to abolish slavery, as noted by historian Lilia Schwarcz in the book Dictionary of Slavery and Freedom (2018), which she co-authored with Flávio dos Santos Gomes.

Speaking to CENARIUM, historian Juarez Silva Júnior noted that emancipation did not bring the necessary affirmative policies for the population enslaved for 350 years. “It resulted in a non-emancipatory act, of mere abolition, without any assertion of rights or reparations to the freed people. The Lei Áurea was the shortest law in Brazilian history, and that was no coincidence,” Juarez Silva remarked.

The scholar added that 13 May is still considered a commemorative date, when it should be one of reflection. “Even with the popularisation of 20 November as ‘Black Consciousness Day’, many still do not understand why 13 May lost its status as a celebratory date,” he said.

For Luciana Brito, who holds a PhD in History from the University of São Paulo and is a professor at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia, in an interview with Folhapress, the abolition occurred without reparations, freedom came without income, and migration to cities happened without housing rights.

“What kind of abolition is this, which came without citizenship, without the right to schooling, without access to land and without employment, but brought violence and the criminalisation of Black people and their everyday and cultural practices?” asks Luciana Brito.

“Of course, 13 May has an important role for the Brazilian Black population. An official law was created that ended slavery. But the next day leaves a legacy that continues to drag on even today for people who are already far removed from slavery in legal terms,” she says.

External Pressures

Although traditionally associated with a humanitarian advance, the Abolition of Slavery in Brazil, on 13 May 1888, was, in practice, the result of economic pressures. For 350 years, Brazil’s economy was tied to enslaved labour: exploitation of Brazilwood, extraction of gold and precious stones, sugarcane, cattle ranching, and coffee plantations.

History teacher Cleomar Lima, who has 40 years of teaching experience, cites two pressures that led to abolition, both involving the English. In the first, after Brazil’s Independence and the return of the then-Prince Regent Dom Pedro I to Portugal, the Regency turned to England after the Bank of Brazil was liquidated. On that occasion, the end of the international slave trade to Brazil was demanded.

Later, as a result of the Paraguayan War (1864–1870), the country again turned to England, when it received a new ultimatum. “Either end slavery, or there will be no further help, you see? So, Dom Pedro I faked an illness, took leave from government and placed his wife, his daughter [Princess Isabel], as regent. She was a woman, he ordered her to end slavery, and no one would notice anything. And on 13 May 1888, it was a Sunday, at the time when people were going to mass, the princess signed the Lei Áurea,” explained Cleomar Lima.

Historian Juarez Silva Júnior adds: “The abolition had been in the making for nearly four decades when it occurred, and largely due to economic pressure from England and its market interests. A whole gradual process, surrounded by oligarchic and political resistance, took place before 13 May.”

Demands

Since Independence in 1822, England had been demanding explicit actions from the Brazilian government to end trafficking. In response, in 1831, a law was passed declaring free all Africans disembarked at Brazilian ports after that year, but it was disrespected.

In the face of the new independent country’s disobedience, England passed the Aberdeen Act in 1845 to repress the international slave trade. Brazil still resisted for some years, but in 1850, after several English actions against Brazilian ships, the Eusébio de Queirós Law was passed, which ended the trade to Brazil.

These were followed by the enactment of the Free Womb Law, passed on 28 September 1871, which declared free the children of enslaved women born from that date onward, and the Sexagenarian Law, which granted freedom to enslaved people over 60 years old in Brazil.

All culminated in the Lei Áurea, or Law 3,353, of 13 May 1888, sanctioned by Princess Isabel, which declared slavery abolished throughout Brazilian territory.