Indigenous peoples must be compensated for hydroelectric plant damages until Congress decides

26 de June de 2025

By Ana Cláudia Leocádio – From Cenarium

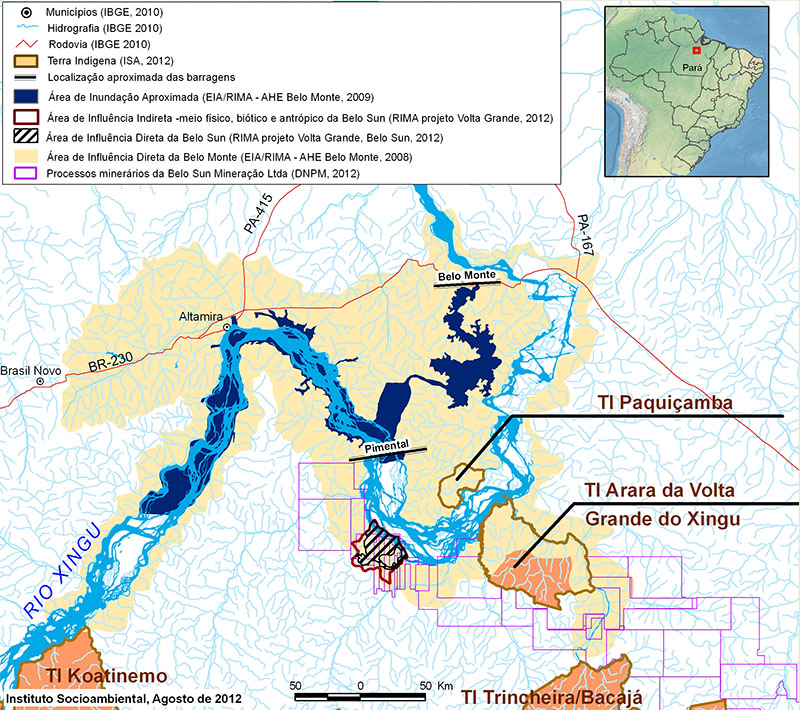

MANAUS (AM) – In a unanimous decision, the Federal Supreme Court (STF) upheld an injunction issued in March by Justice Flávio Dino, granting the National Congress two years to regulate the participation of Indigenous peoples in the proceeds from the exploitation of mineral and water resources in their territories, such as those impacted by the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant (UHBM) on the Xingu River in Pará. The decision was made in a virtual plenary session concluded this Tuesday, the 24th, and until a legal framework is established, companies must financially compensate Indigenous peoples affected by such projects.

The ruling was issued within the scope of injunction writ No. 7490, filed by the Yudja Miratu Association of Volta Grande do Xingu and six other entities representing Indigenous peoples living along the Xingu River, which hosts the hydroelectric dam in the state of Pará. The injunction writ is a legal mechanism used when a constitutional right cannot be exercised due to the lack of specific regulatory legislation. The action was filed on January 7 of this year.

Justice Flávio Dino, rapporteur of the case, stated that the alleged omission concerns the specific conditions for conducting research and extraction of mineral resources, as well as the use of hydraulic energy potentials in Indigenous lands, as outlined in § 1 of Article 176 of the Federal Constitution, and the manner of Indigenous participation in the results of resource exploitation, as provided in § 3 of Article 231 of the Constitution.

According to Dino, since the Constitution’s enactment in 1988, the National Congress has failed to regulate these provisions, and the existence of pending bills does not equate to specific legislation, thereby confirming the omission claimed by the Indigenous associations.

The Belo Monte Plant was built and inaugurated in November 2015 without proper consultation with Indigenous peoples, as required by current legislation, and has faced a series of legal challenges, including by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF). In a special appeal reviewed by the STF, with Justice Alexandre de Moraes as rapporteur, the justices decided not to revoke the license that allowed the project, citing the risk of significant financial losses to the public coffers, but ruled that Indigenous peoples must be compensated for the resulting damages.

In their petition, the Indigenous associations asked the Supreme Court to mandate that, in light of the legislative omission, the communities affected by the Belo Monte Plant receive 50% of the total amount owed to States, the Federal District, Municipalities, and federal agencies as financial compensation for the use of water resources, including energy potentials, as stipulated by Decree-Law 227/67.

The decision

In his vote, upheld by the justices on Tuesday, the 24th, Flávio Dino acknowledged Congress’s omission and gave lawmakers a 24-month deadline to regulate the constitutional provisions. The ruling also sets out specific criteria for Belo Monte to follow in compensating Indigenous peoples for the damages caused until congressional regulation is established.

Dino’s injunction also recognizes that projects designed to harness water resources in Indigenous territories have impacts beyond their physical location, they need not be built within the land itself to cause harm.

Based on that principle, until the legislative gap is addressed, all such projects authorized by the Union or Congress must comply with specific conditions, such as conducting studies on the impacts on Indigenous economic activities and establishing forms of redress, along with mechanisms to ensure Indigenous participation in the economic outcomes of the companies involved.

Dino stressed that his decision “does not authorize new exploitation of energy potentials on Indigenous territories,” as such activities still require compliance with all constitutional and legal requirements, including ILO Convention 169.

“The scope of this judicial decision is limited to addressing constitutional omissions, establishing the conditions under which Indigenous peoples may participate in activities that affect their lands, so that they cease to be merely victims and instead become beneficiaries,” emphasized the justice.

In the ruling, the magistrate gave the Union and the National Congress ten days to submit statements. He also ordered Norte Energia S.A., the company responsible for the Belo Monte Plant, to be notified in case it wishes to comment in the case file. The company informed CENARIUM that it will not comment on the STF’s decision.

Other bodies notified include the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai), the National Electric Energy Agency (Aneel), as well as the State of Pará and the municipalities of Altamira, Vitória do Xingu, and Brasil Novo. Aneel has 15 days to comment on the energy produced by Belo Monte and its implications for the Financial Compensation for the Use of Water Resources (CFURH).

Situation in other countries

In his vote, Flávio Dino cited examples from three countries where Indigenous peoples are compensated for damages but clarified that there is no ready-made solution that can be simply imported to Brazil. The goal is to find a fair way to redress the impacts caused by natural resource exploitation in Indigenous territories and the disruption of their traditional way of life.

In Australia, for example, “compensation payments for damage to Indigenous lands or to the peoples themselves as a result of mineral exploitation are set through agreements between the requesting companies and Indigenous groups, taking into account the mineral’s value, land use deprivation, and loss of improvements.”

In Canada, although current law (Indian Act30) secures reserves for Indigenous groups, it also defines them as federal territory. Thus, “the government is free to decide when and how to use natural and underground resources,” but it also ensures that a portion of the revenues from this exploitation is allocated to Indigenous peoples, similar to a profit-sharing model.

In New Zealand, mining on Māori lands “is subject to an agreement between the license holder and the Indigenous peoples, and must cover, among other elements, compensation for losses or damages, reimbursement of all reasonable costs and expenses incurred by the landowner due to the negotiations, and compensation for loss of income, privacy, and amenities.”

Petitioners in the STF injunction:

- Yudjá Miratu Association of Volta Grande do Xingu

- Juruna Unidos Indigenous Association of Volta Grande do Xingu

- Korina Juruna Indigenous Association of Paquiçamba Village

- Arara Unidos Indigenous Association of Volta Grande do Xingu

- Arara do Maia Indigenous Resistance Association

- Bebô Xikrin do Bacajá Association – ABEX

- Berê Xikrin Indigenous Association of the Bacajá IT

Read the full vote by Justice Flávio Dino: