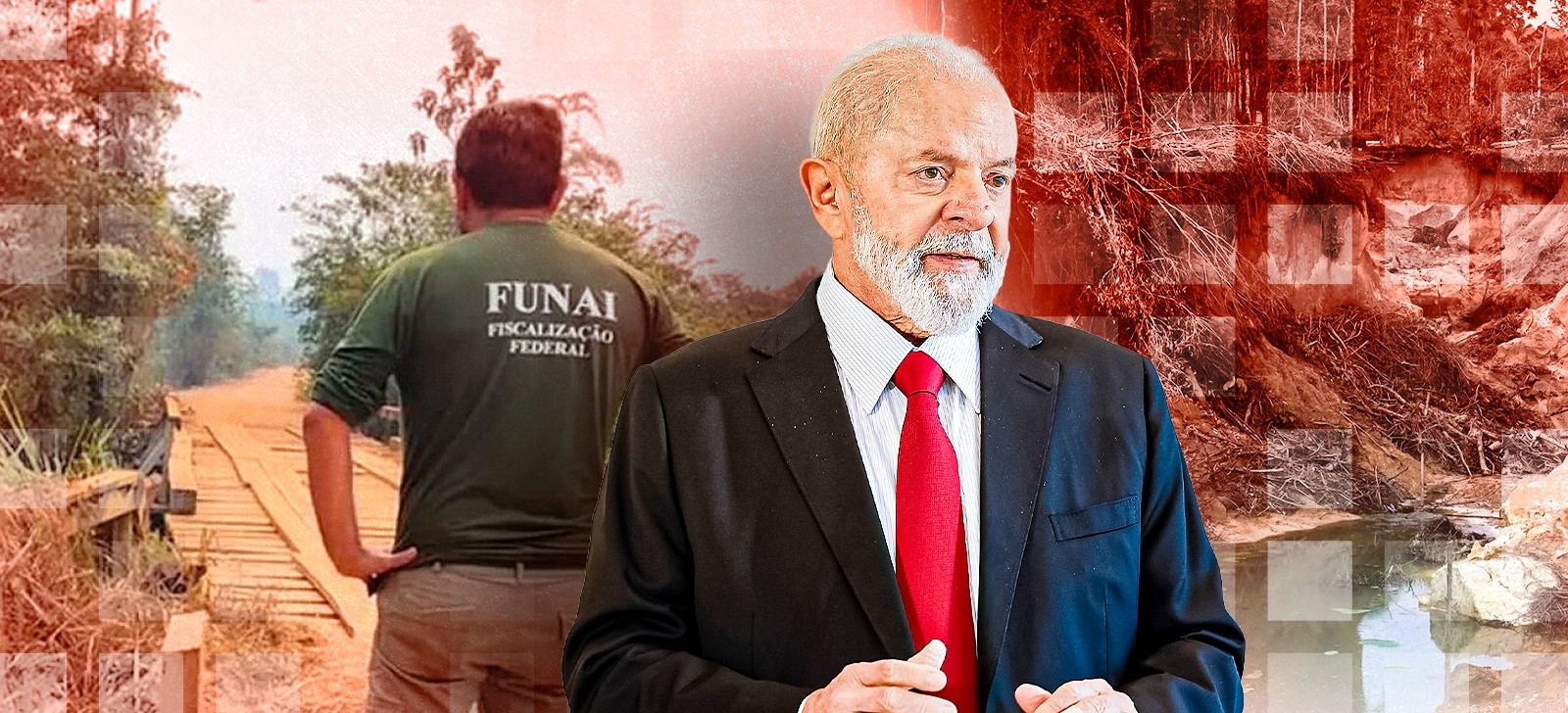

President of Brazil regulates police power of Indigenous Agency

04 de February de 2025

By Ana Cláudia Leocádio – From Cenarium

BRASÍLIA (DF) – A decree signed by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva regulates the police power of the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai) over Indigenous lands and areas subject to usage restriction ordinances to protect the rights of these peoples. The document was published on Monday, the 3rd, in the Official Gazette and complies with a ruling by the Supreme Federal Court (STF), which upheld an action filed by the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib).

Outlined in Article 1, item VII, paragraph ‘d’ of Law 5.371/1967, which established Funai, this police power had never been regulated. Decree No. 12,373, signed by Lula, also draws from provisions in the “Indian Statute” (Law 6.001/1973) and the Temporal Framework Law (Law 14.701/2023).

From now on, Funai agents will be authorized, among other duties, to seize assets or seal off facilities used in the commission of infractions, as well as, in exceptional cases, to destroy, render useless, or allocate goods used in illegal activities.

The decree also defines the objectives of Funai’s police power, including preventing and deterring violations or threats to Indigenous rights, preventing and deterring illegal occupation by third parties on Indigenous lands, and executing police consent in cases provided by law.

Article 3 of the decree establishes violations against Indigenous rights, which range from non-Indigenous entry into Indigenous lands to the destruction of Indigenous property or alteration of territorial boundaries, as well as damage to or removal of boundary markers and plaques.

The decree further states that Funai “may request cooperation from public security agencies, especially the Federal Police, the Armed Forces, and auxiliary forces, to ensure the protection of Indigenous communities, their physical and moral integrity, and their assets, when necessary for security operations.”

“During the administrative process of investigating violations against Indigenous rights, Funai must conduct inspections, prepare detailed reports, and forward them, when applicable, to competent public agencies or entities, including for the purpose of initiating legal actions,” the document states.

Signed on the final deadline set by the STF, January 31, 2025, the decree takes effect upon its publication. CENARIUM has reached out to Funai for information on how these new measures will be implemented in Indigenous territories and is awaiting a response.

Supreme Court Orders Government to Regulate

In July 2020, Apib filed Argument of Noncompliance with a Fundamental Precept (ADPF) 709 with the STF, citing actions and omissions by the government regarding the protection of Indigenous rights during the administration of former President Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022).

In November 2023, the case’s rapporteur, Justice Luiz Roberto Barroso, ordered the federal government to present, within 60 days, a new plan for the removal of invaders from seven Indigenous Territories (ITs), including goals, indicators, deadlines, expected results, a responsibility matrix, and resources to be used in the operations.

In a December 20, 2024 decision, Barroso gave the government until January 31, 2025, to regulate Funai’s police power. In his ruling, the minister noted that he took this action because the federal government had failed to comply with a previous decision on the matter, issued on March 5, 2024, despite an extension until October 21 of the same year.

During the legal proceedings, the government argued that the documents and drafts related to Funai’s police power regulation were classified under relevant legislation. The federal administration committed to publishing the decree by January 31, 2025, but requested an additional 60-day extension.

In a brief ruling, Barroso rejected the government’s arguments outright, stating: “If this [regulation] does not occur, I order that all preparatory documents be attached to the case files, including the legal opinions of the involved agencies, even if under sealed petition.”

Barroso further emphasized that “the regulation of Indigenous police power does not diminish the competence of other environmental agencies.” “On the contrary, Funai and Ibama can exercise police power in Indigenous lands in a coordinated and collaborative manner. This level of coordination is commonly practiced between federal and state environmental agencies, and there is no reason why it should not apply between two agencies of the same federal level”, he stated in his December 2024 ruling.

Focus on the Vale do Javari

In 2020, when Apib filed ADPF 709, the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Vale do Javari (Univaja) requested to join the case as an “amicus curiae” (friend of the court), arguing that “the Vale do Javari region has the highest concentration of isolated Indigenous peoples and recent contact groups in the country.” The organization highlighted that such groups are particularly vulnerable and have specific needs.

On June 5, 2022, Brazilian Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips were brutally murdered in the Vale do Javari. Their bodies were only found ten days after their disappearance. A Federal Police forensic report revealed that Dom Phillips was killed by a gunshot from a hunting weapon, while Bruno Pereira was shot three times, one of them in the face.

The murders brought international attention to the Alto Solimões region, near the Peruvian border, where Univaja operates a community-led surveillance project, carried out by Indigenous people themselves. Bruno Pereira had collaborated on this initiative and ultimately lost his life for it.

Measures Funai Can Take Under the Decree:

I – Prohibit or restrict third-party access to Indigenous lands for a determined and renewable period;

II – Issue precautionary notifications to violators, informing them of their offense and setting a deadline for voluntary compliance or removal, under penalty of subsequent administrative or judicial enforcement measures;

III – Order the compulsory removal of third parties from Indigenous lands if there is evidence of harm or imminent risk to Indigenous peoples or their lands;

IV – Restrict access and movement of third parties in Indigenous lands and areas where the presence of isolated Indigenous groups is confirmed, as per Article 7 of Decree No. 1,775, of January 8, 1996;

V – Request cooperation from other authorities or public control and enforcement agencies, in compliance with their respective legal powers;

VI – Seize assets or seal off private facilities used in the commission of violations; and

VII – In exceptional cases, destroy, render useless, or allocate goods used in illegal activities.