Yanomami women and children face vulnerability on the streets of Brazil

10 de July de 2025

By Iuri Carvalho – From Cenarium

BOA VISTA (RR) – Located in Brazil’s far north, Boa Vista (RR) marks its 135th anniversary this July 9. Amid the celebrations, one group remains nearly invisible in the city, despite occupying its busiest streets: the Yanomami Indigenous people, who travel from their communities in search of assistance but end up surviving on the streets without housing, food, or any form of support, as shown in videos obtained by CENARIUM.

Anyone passing daily under the Pery Lago Overpass can see these groups gathered around the “Feira do Produtor” (Producer’s Market) in the West Zone of the capital, which has become a makeshift shelter for Indigenous people living in vulnerable conditions. They tie hammocks to sidewalks and unused structures at the market.

Videos show mothers and children lying on sidewalks in broad daylight. The children appear malnourished, and some are unclothed, exposed to passersby on foot or in vehicles. They are accompanied by women who seem to share the same living conditions.

In another video, Indigenous people, including children, are seen in garbage heaps at the open-air market. There, they tie hammocks and eat leftover food—often repeatedly. One person appears nearly naked, lying on the dirty ground, while business continues normally inside the market and cars drive by outside.

A vendor, who asked to remain anonymous, told reporters that the situation has become routine and it’s unclear which agency is responsible. “No one knows if there’s really an agency in charge, because they end up creating a lot of disruption for businesses. There’s also the issue of bad smells, filth, and malnourished children,” she said.

What the MPF and Funai say

According to the Federal Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), the agency has held hearings and meetings to understand the cause of the cyclical migration and permanence of Indigenous people in the capital, which mostly occurs due to alcohol abuse.

Following a series of recommendations, the issue became the subject of a public civil action, which has already been ruled on and complied with, requiring the construction of a base in the Indigenous territory and a health center for treatment of alcoholism and other conditions linked to unregulated contact with broader society.

“The MPF worked in partnership with child protection councils and other federal, state, and municipal agencies to develop protocols for approach, care, and referral of individuals in these situations. These actions significantly reduced the phenomenon, which nevertheless continues due to the Indigenous peoples’ constitutional right to freedom of movement,” the office said.

The National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai) stated that it is aware of the presence of these Indigenous groups and that the Producer’s Market is a transit point for buying tools and supplies, selling goods, visiting relatives, and accessing services like banking and social benefits.

“The right to movement cannot and should not be violated. As previously clarified, Funai carries out various actions so that, when it is their wish, these groups can return to their communities, including efforts to convince them to do so given the risks they face. When they still choose to remain in the city, inter-institutional coordination with the state and municipalities aims to strengthen their security and protect their health and social well-being,” the agency stated.

Funai also reported that it has been coordinating with the Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger (MDS) and the Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship (MDHC) to establish a care protocol for Indigenous groups in urban transit.

“In Boa Vista, coordination with social and health protection networks is ongoing, as is the daily service provided by the social workers contracted by the Indigenous affairs agency. These professionals distribute daily meals to ensure food security for the groups present and also respond to other urgent needs,” Funai stated.

Sociologist Linoberg Almeida believes the discomfort some feel when seeing people in street situations is not caused by the individuals themselves, but is amplified by hate speech in public discourse—that is, speech that dehumanizes and alienates these people from social coexistence. He argues that more debate is needed to find solutions to lift Indigenous people out of vulnerability.

“What creates visual discomfort in cities is often hate speech in public opinion, which fosters barriers and a certain distance between unhoused people and the general population, fueling ignorance, prejudice, disdain, hostility, and aversion. When they are Indigenous, this is compounded by stereotyped and discriminatory views. Frankly, we must expand dialogue and hearings—but also go beyond them. Politicians, researchers, civil society, businesspeople, and Indigenous peoples need to commit and be held accountable,” he said.

Indigenous health

The Yanomami Indigenous Territory (IT) spans 10 million hectares, making it Brazil’s largest Indigenous territory, straddling the states of Amazonas and Roraima. A total of 33,300 Indigenous people live in the region, spread across 399 communities.

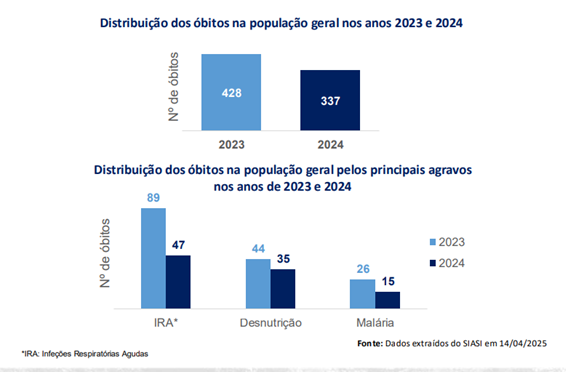

This year, the Yanomami Emergency Operations Center (COE) Bulletin reported a 21% reduction in Indigenous deaths in 2024 compared to the previous year, when the federal government recognized a severe public health crisis in the demarcated territory. According to COE data, 428 deaths were recorded in 2023—91 more than in 2024. The main causes of death were acute respiratory infections (ARIs), followed by malnutrition and malaria.

Amid child malnutrition among Indigenous children in Boa Vista, the bulletin shows that in 2024, 35 people died due to this cause, down from 44 deaths in 2023. In this nutritional context, monitoring of children under age 5 by the Food and Nutrition Surveillance System increased, improving health outcomes for these patients.

According to a May 5 report from the Ministry of Health, the collapse of Indigenous health services up until 2022 resulted in an emergency situation due to lack of assistance in the Yanomami Territory, leading to severe underreporting of diseases and deaths.

When the Yanomami health emergency was declared, only 690 health professionals were employed. That number has since increased by 158%, ensuring 1,700 professionals are now working on rotation in the territory and in Indigenous Health Houses (Casai).

The municipality of Boa Vista also reported that its Indigenous health services follow national policy guidelines: “Providing differentiated care that respects the cultural, social, and territorial particularities of each Indigenous group. At Santo Antônio Children’s Hospital, meals are tailored to the dietary habits of each ethnicity, and the ward is equipped with hammocks and a culturally appropriate environment. On average, 410 children are treated monthly, of whom 125 are hospitalized,” the city government stated.