Amazon for sale? BR-319: Narratives, business and power

11 de March de 2025

By Marcela Leiros – From Cenarium

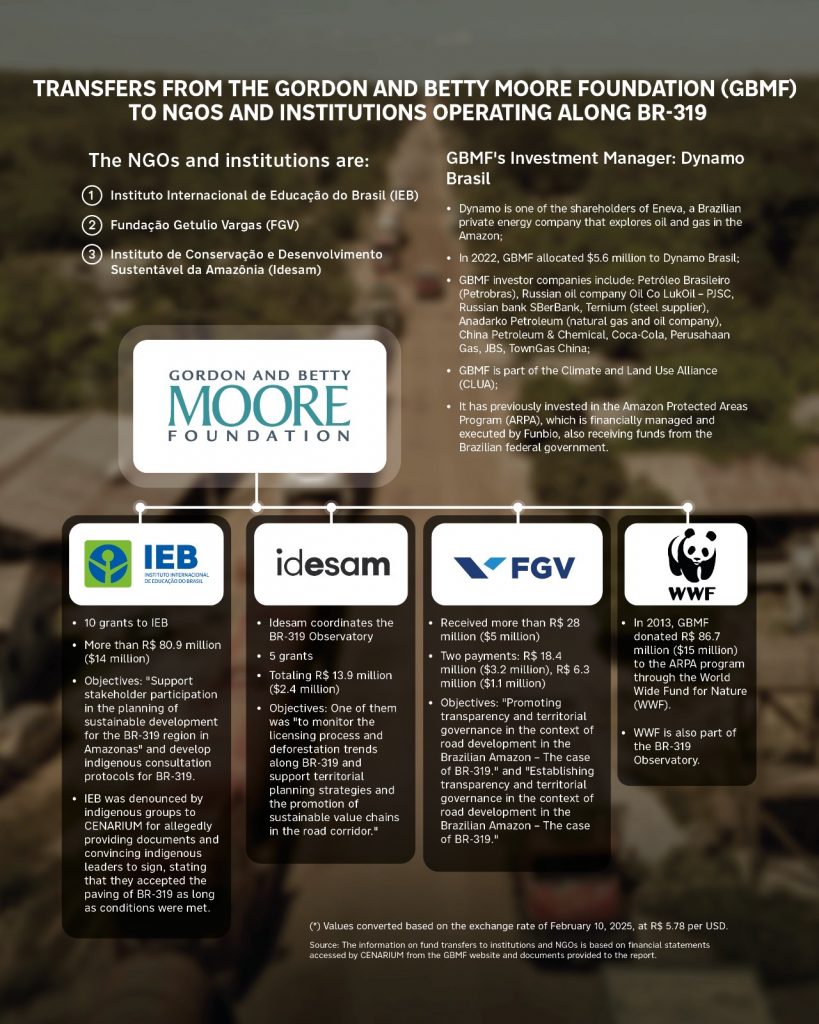

MANAUS (AM) – Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and institutions developing projects related to the BR-319 have received, collectively, over R$ 122.8 million (equivalent to more than US$ 21.4 million* at the current exchange rate) from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF) over the past 15 years. This international institution is linked to enterprises that impact the forest, such as fossil fuel extraction in the Amazon by Eneva S/A. These same NGOs and institutions aim to control the narrative of BR-319 through governance with the goal of obtaining more decision-making power over the highway then the State itself.

The report was based on information published in the article “Environmental Disaster in the Amazon and Violation of Indigenous Rights Facilitated by Governance Projects on BR-319,” authored by biologists and researchers Lucas Ferrante and Philip Fearnside, along with journalist and writer Monica Piccinini, CENARIUM’s correspondent in London. The report also conducted a six-month investigation. Information on the transfers to institutions and NGOs is detailed in financial statements, data available on the GBMF website and documents sent to the editorial office.

The Organizations identified as direct recipients of funds from the international corporation and which developed projects related to governance on the BR-319 include the Instituto Internacional de Educação do Brasil (IEB), Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV), and the Instituto de Conservação e Desenvolvimento Sustentável da Amazônia (Idesam). The financial statements also include a donation from GBMF to the Amazon Protected Areas Program (Arpa), made through the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

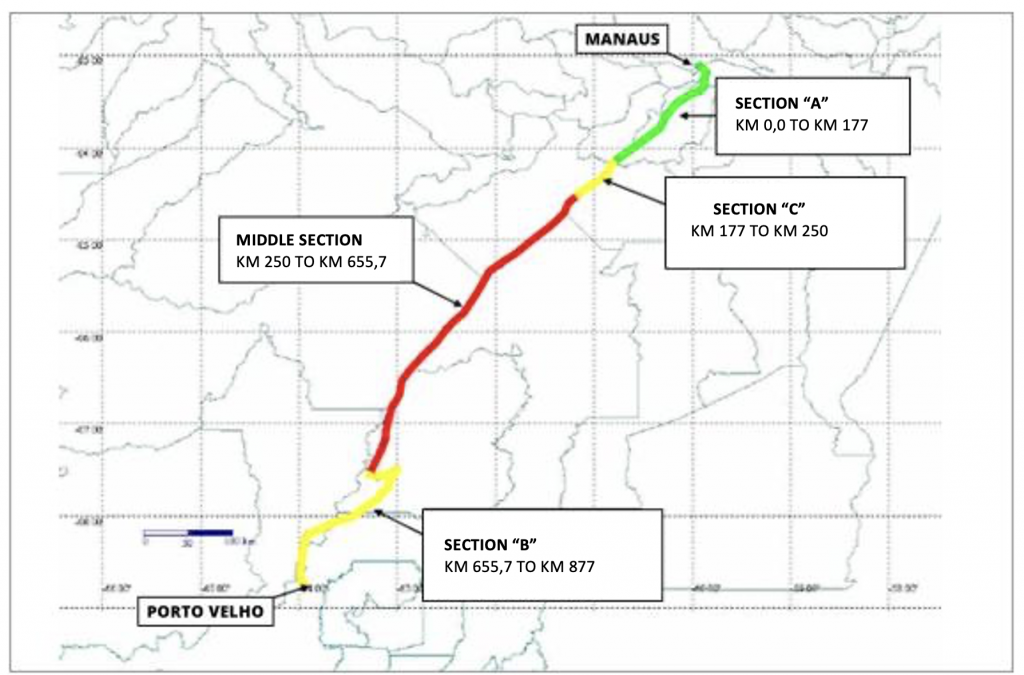

The highway, which spans 885 kilometres, connecting Manaus (AM) to Porto Velho (RO), has a history fraught with controversy due to environmental, social, and economic concerns—particularly in the section between kilometres 250 and 655, known as the “Middle Section,” which has become nearly impassable. The road’s reopening and repaving have sparked debates between those arguing its infeasibility and those asserting that security could be ensured through proper oversight.

Allocations to IEB

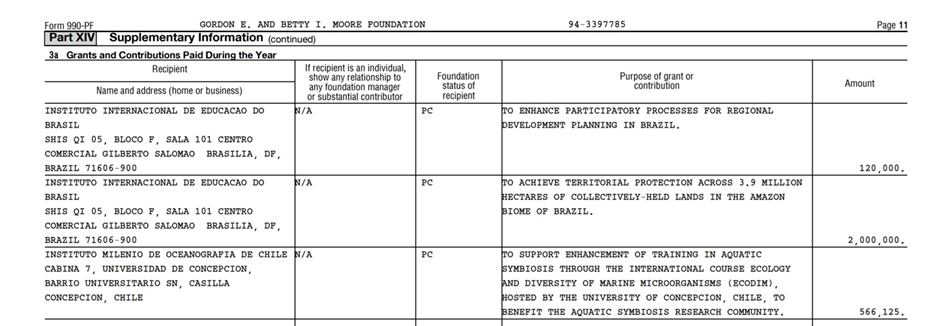

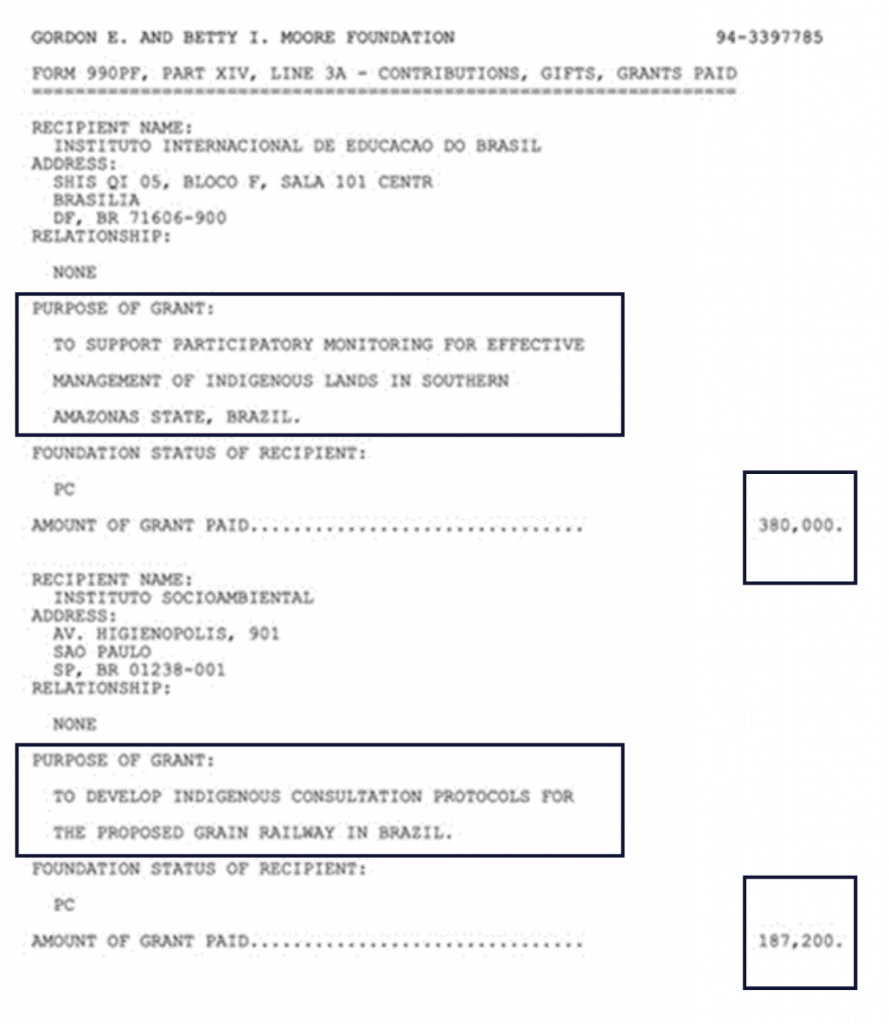

Among the funds granted by GBMF to NGOs and institutions involved in BR-319 projects, at least ten grants have been directed to IEB, surpassing R$ 80.9 million—equivalent to US$ 14 million—since 2004. The institute has been denounced by Indigenous groups to CENARIUM for allegedly providing documents and persuading leaders to sign agreements stating that they accepted the BR-319’s repaving, provided certain conditions were met. However, Indigenous communities have vehemently opposed the project.

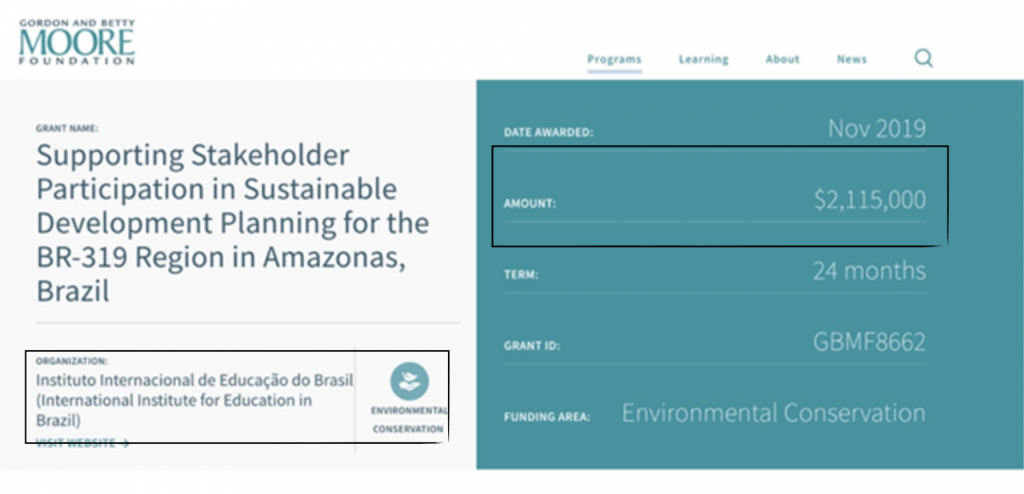

One of these allocations, amounting to R$ 12.2 million (US$ 2.1 million), was designated in 2019 to “support stakeholder participation in sustainable development planning for the BR-319 region in Amazonas.” This figure is publicly available on the foundation’s website.

Out of this substantial sum, R$ 3.2 million (US$ 567,000) was specifically allocated for the development of Indigenous consultation protocols regarding the BR-319.

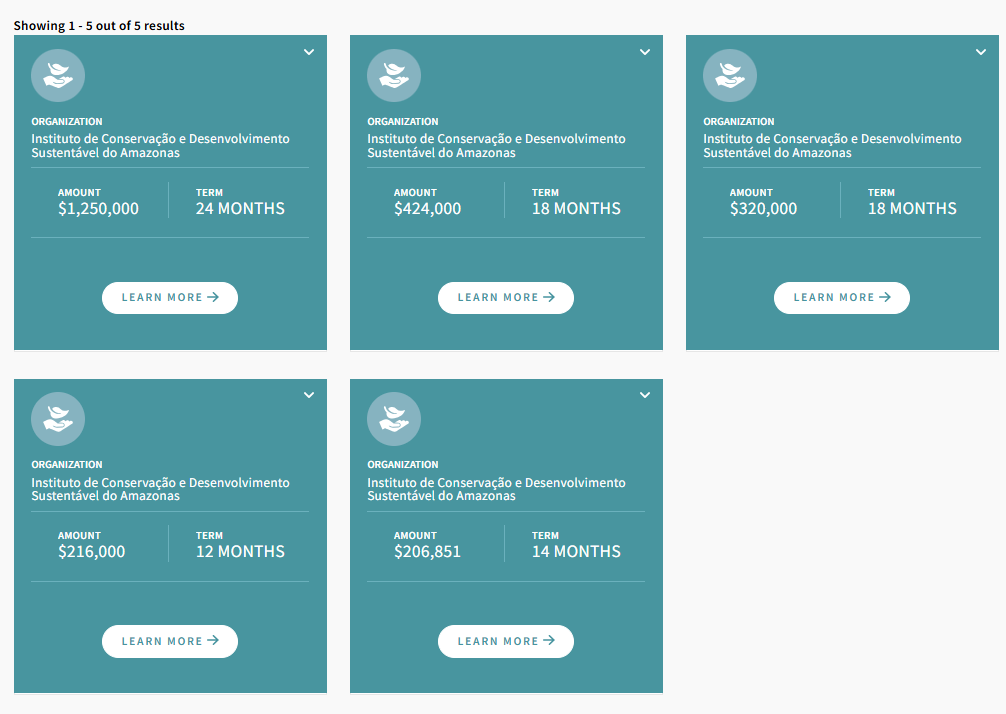

Funding for Idesam

The GBMF has also provided funding to Idesam. Five grants were made between 2011 and 2023, totalling R$ 13.9 million (US$ 2.4 million), with more than half received in November 2023. The largest amount was allocated to “monitor the licensing process and deforestation trends along the BR-319 and support territorial planning strategies and the promotion of sustainable value chains in the road corridor.”

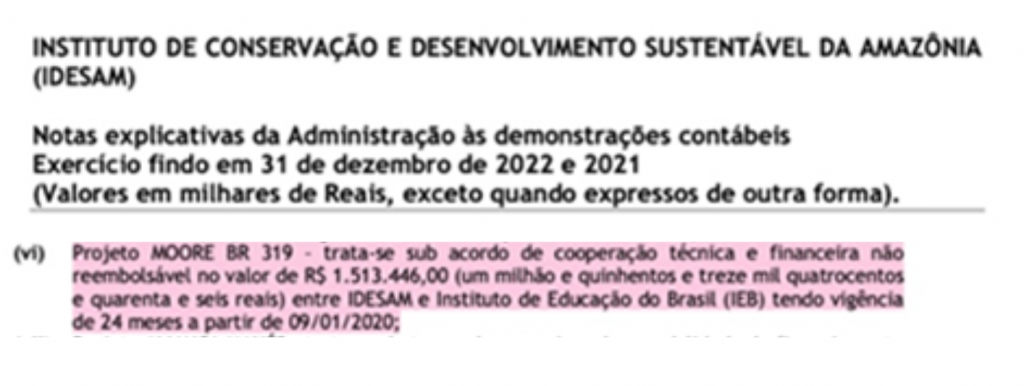

One of the grants was directed to the project entitled “Projeto Moore BR-319,” a non-repayable sub-agreement for technical and financial cooperation worth R$ 8.7 million (US$ 1.5 million) between Idesam and IEB, with a duration of 24 months from 2020.

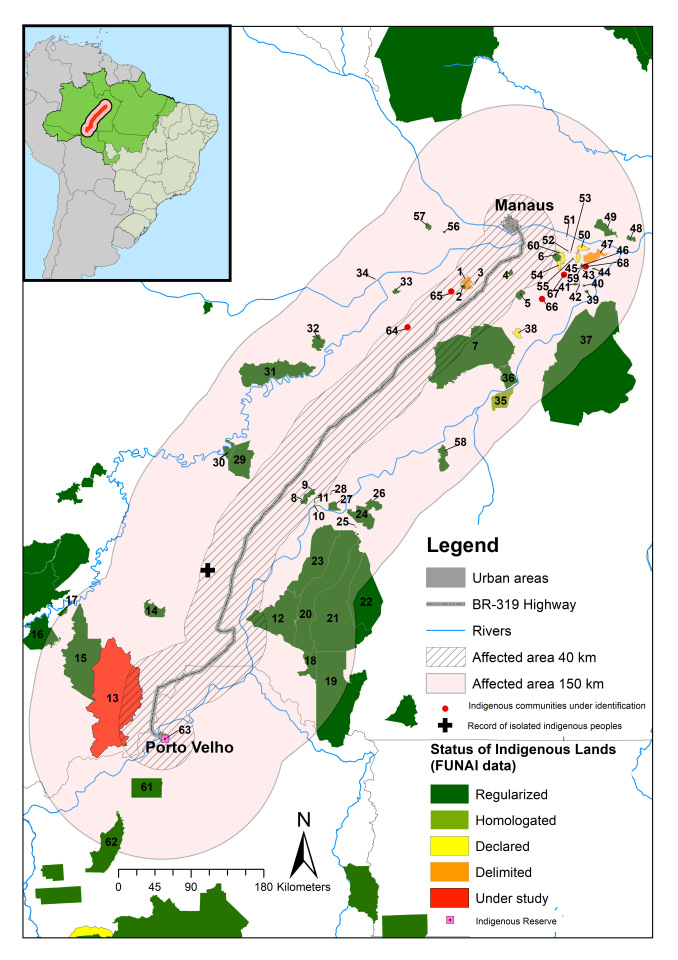

Headquartered in Manaus, Idesam coordinates the BR-319 Observatory, a network of civil society organizations operating in the area influenced by the BR-319, comprising 13 municipalities, 42 Conservation Units, and 69 indigenous groups, including 63 officially recognised Indigenous Territories (IT), five unrecognised communities, and a population of isolated peoples within a 150-kilometre range, according to a scientific article published in Land Use Policy. The network’s activities aim to produce information on the road and the necessary processes for what it calls “inclusive development.”

The BR-319 Observatory has conducted studies presenting positive indicators related to the highway and supports the development of a territorial governance plan along the road that crosses the Amazon. A report from the group, titled Retrospective 2023: Deforestation and Heat Spots in the BR-319 Influence Area, indicated that in 2023, areas monitored by the observatory within the road’s impact zone recorded a sharp decline in deforestation.

Another report, titled “Analysis of the Implementation of Conservation Units Under the Influence of the BR-319”, conducted by Idesam in partnership with the Brazilian Biodiversity Fund (Funbio), highlights the benefits and opportunities that the reconstruction of the BR-319 would bring to the region.

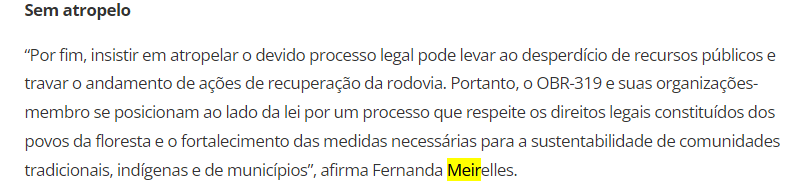

In the media, support for the BR-319 has also been expressed. The former Public Policy Coordinator at Idesam and former Executive Secretary of the BR-319 Observatory (OBR-319), Fernanda Meirelles, stated in an interview published on 3 April 2024 that the organization was not against the repaving or any works on the BR-319 but defended that the legal framework concerning socio-environmental legislation should be respected.

Idesam’s position became clearer after the Federal Court of Amazonas suspended the preliminary license granted by the National Department of Transport Infrastructure (Dnit) for the BR-319, following a request from the Climate Observatory. The institute then broke away from the coalition of 120 Brazilian civil society organizations.

On 29 July 2024, Idesam published a statement on its website regarding the BR-319, in which it declared: “Idesam is not against the BR-319. As a civil society organization, it works to promote social and economic development and the conservation of forests in the Brazilian Amazon. Regarding the BR-319, Idesam supports repaving through a rigorous licensing process, respecting legislation and its social and environmental safeguards. This is Idesam’s position.”

Idesam also coordinates Amaz, a project that claims to seek businesses generating positive impacts in rural and forested areas of the Amazon. In 2023, the impact accelerator, alongside entities such as Fundo Vale (a fund created by the mining company Vale, which extracts iron ore in Pará and has been involved in the socio-environmental disasters in Brumadinho and Mariana, both in Minas Gerais) and the JBS Amazon Fund (of the Brazilian company JBS, one of the world’s largest meat processing firms), announced that they would offer up to R$ 600,000 to startups willing to establish businesses in the Amazon rainforest.

The accelerator’s “founders and strategic partners” include, in addition to Fundo Vale and the JBS Amazon Fund, the Instituto Humanize, Instituto Clima e Sociedade (ICS), Good Energies Foundation, and the Plataforma Parceiros pela Amazônia (PPA). Amaz lists its partners as Move.Social, Sense-Lab, Mercado Livre, ICE, SBSA Advogados, Costa Brasil, Climate Ventures, and private investors. These details are available on the Amaz website.

“This goes beyond contradiction—it is a clear conflict of interest. Amaz, the largest investment accelerator in the North, is coordinated by Idesam, which is also involved in discussions on repaving a road that would stimulate business in the region. This connection benefits Amaz, managed by Idesam, compromising impartiality in assessing environmental and socio-economic impacts and raising serious concerns about transparency and governance,” states researcher Lucas Ferrante.

FGV

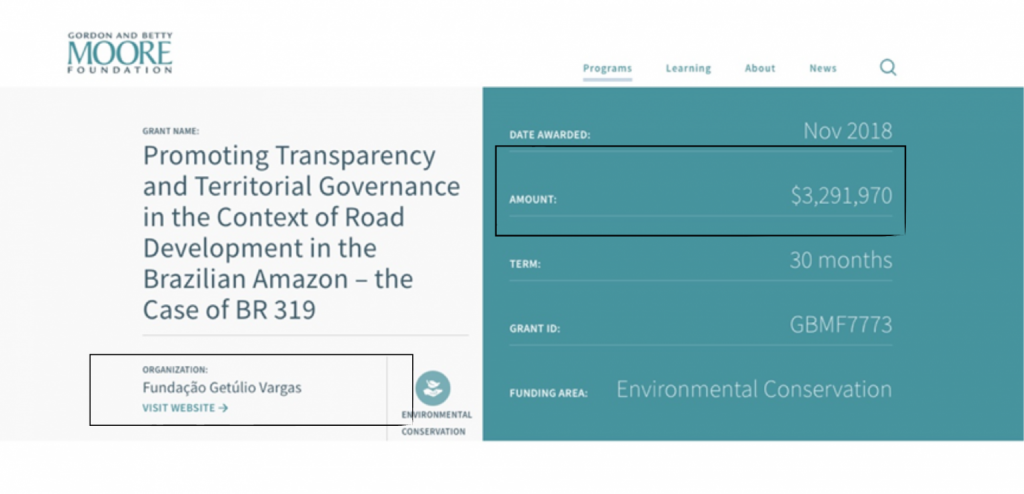

In the same sense of addressing positive possibilities regarding the reopening of the highway that crosses the Amazon, FGV published in 2019 the project titled “Promoting transparency and territorial governance in the context of highways installation in the Amazon – the case of BR-319,” funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

The project’s objective was, according to the entity, “to develop parameters for adopting a human rights-based approach aimed at preventing abuses and socio-environmental violations throughout the decision-making process for major infrastructure projects in Brazil, especially in the case of BR-319, along its entire extension.” This information is available on FGV’s website.

However, the initiative was the target of denunciations by scientists. In 2021, researchers Lucas Ferrante and Philip Martin Fearnside alerted the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF) that the project violated the rights of indigenous peoples guaranteed by Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO) — to which Brazil is a signatory — and by Brazilian legislation.

ILO Convention 169 addresses the right of traditional populations to free, prior, and informed consultation for projects that significantly impact their ways of life. The consultation must be carried out by governments with the concerned peoples through their legitimate representatives and in the manner the communities deem best.

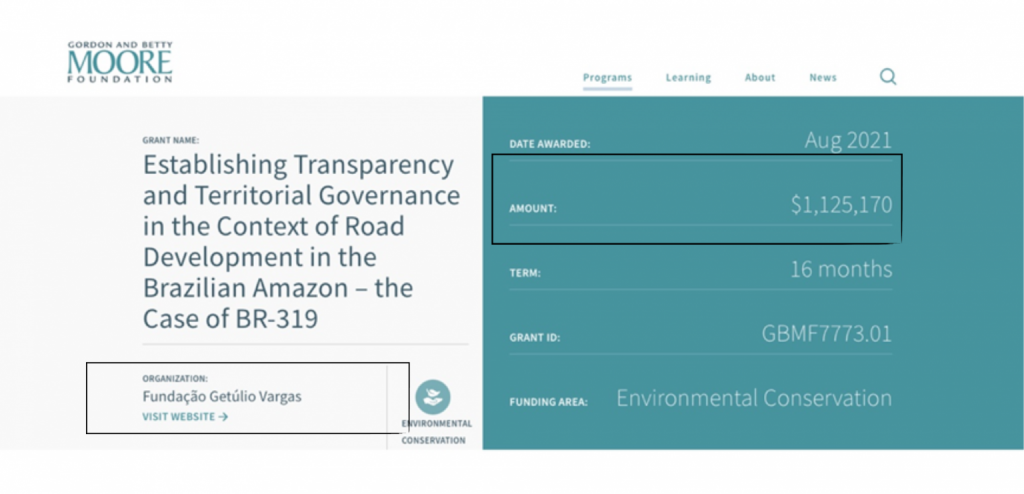

FGV also received transfers from GBMF. The amounts directed exclusively to the foundation, since 2018, exceed R$ 28 million (US$ 5 million). Two payments, of R$ 18.4 million (US$ 3.2 million) and R$ 6.3 million (US$ 1.1 million), respectively, were described as: “Promoting transparency and territorial governance in the context of road development in the Brazilian Amazon – The case of BR-319” and “Establishing transparency and territorial governance in the context of road development in the Brazilian Amazon – The case of BR-319.”

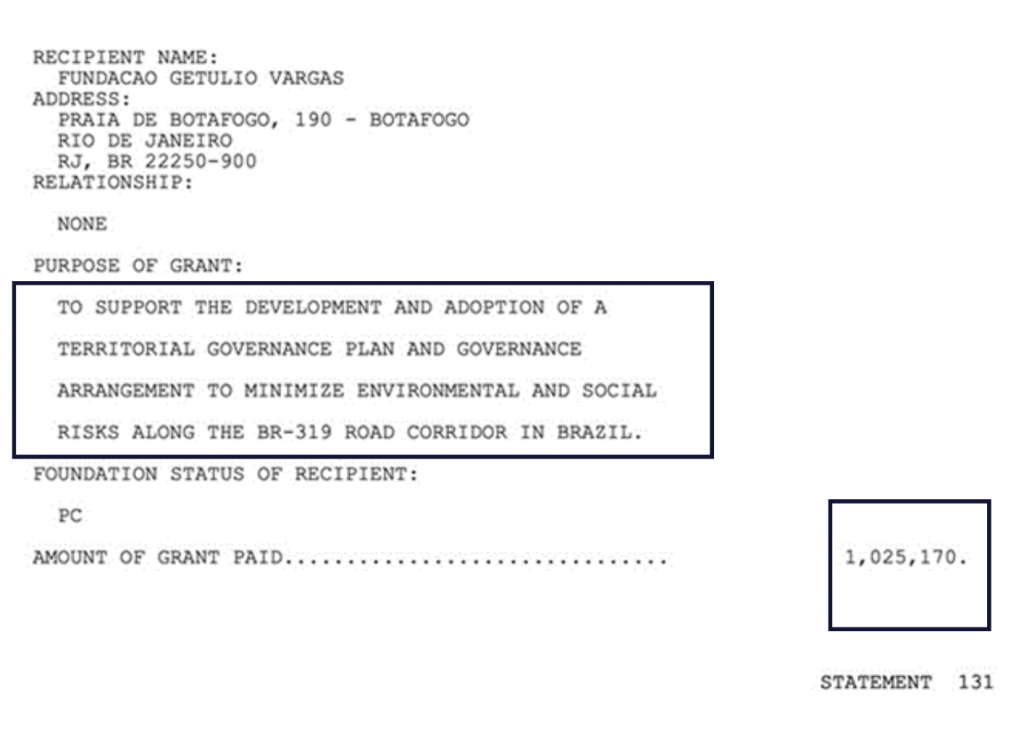

Another document, amounting to R$ 5.9 million (US$ 1.025 million), was allocated to “supporting the development and adoption of a territorial governance plan and a governance arrangement to minimize environmental and social risks along the BR-319 road corridor in Brazil.”

GBMF

It is also worth noting that GBMF’s investment manager is Dynamo Brasil, one of the shareholders of Eneva, a private Brazilian energy company that explores oil and gas in the Amazon and has already obtained, in partnership with Atem Distribuidora, the right to explore four more extraction blocks in the region, in what became known as the “end-of-the-world auction.” Eneva is also a target of MPF, which received reports of death threats against indigenous people, as highlighted in the reportage “The gas that suffocates in the Amazon.”

In 2022, the foundation allocated US$ 5.6 million to Dynamo Brasil. The contribution was directed to the “controlling entity,” as shown by a transfer receipt accessed by CENARIUM.

The exploitation of Eneva’s gas blocks will only be possible with the repaving of the BR-319 highway since the road is one of the main routes providing access to the extraction sites. In the opinion piece “Brazil must reverse gear on Amazon road development,” published in Nature, the world’s leading scientific journal, it was pointed out that the opening of secondary roads and the repaving of BR-319 to facilitate this exploration tend to drive the Amazon to collapse, also triggering climate changes and zoonotic jumps with global consequences.

The lead author of the publication, Lucas Ferrante, emphasizes: “It is not just the BR-319 highway that will provide access to these blocks; there are other roads planned from it, such as AM-366, which connects BR-319 to Tapauá and cuts through the trans-Purus block to Tefé, granting access to large oil and gas exploration blocks in these areas. This will push the Amazon beyond the tolerable deforestation limit, leading to consequences for the climate, loss of biodiversity, impacts on the entire population of Amazonas, including increased epidemics in the region and the risk of a sequence of new global pandemics.”

Some of GBMF’s investments in shares include companies such as Petróleo Brasileiro (Petrobras); the Russian oil company Oil Co LukOil – PJSC; the Russian bank SBerBank; steel supplier Ternium; natural gas and oil company Anadarko Petroleum; China Petroleum & Chemical; Coca-Cola; Perusahaan Gas; JBS; and TownGas China.

Alliance

Donations from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to Brazilian institutions began in 2004, within the context of the Andes-Amazon Initiative. An American foundation, it was created by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore and his wife, Betty Moore, with the mission of “supporting scientific discoveries and environmental conservation,” becoming one of the largest private grant-making foundations in the United States. In 2017, it was recognized as the most generous in the state of California. Among the foundation’s interests is the BR-319 highway.

The foundation, along with the ClimateWorks Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies, and Good Energies by Porticus, is part of the Climate and Land Use Alliance (CLUA). Between 2010 and 2021, CLUA awarded 2,461 grants and contracts aligned with the Alliance for Climate and Land-use Strategy, supporting efforts in Central and South America, including Brazil. According to the organization, the total funding amounted to $738 million (more than R$ 4 billion).

These institutions began investing in Brazil through the Amazon Protected Areas Program (Arpa), created in 2002 and financially managed and implemented by Funbio, a private financial mechanism established in 1996 that operates in partnership with the government and private sectors. According to its own statements, the program’s goal is to support the conservation and sustainable use of 60 million hectares—15% of the Brazilian Amazon—by 2039.

Arpa was structured with financing from the German Development Bank (KfW), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF), the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the Margaret A. Cargill Foundation, Anglo American, the World Bank, the Amazon Fund, the Brazilian government, the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES), and the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (MMA).

In November 2013, the GBMF donated R$ 86.7 million ($15 million) to the Arpa program, via the WWF, to ensure, according to the entity, the protection of 60 million hectares of legally established protected areas. WWF is also part of the BR-319 Observatory.

Funbio‘s funders include companies such as Chevron, PetroRio, ExxonMobil, GBMF, KfW, the Norwegian Embassy, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Votorantim Industrial, Vale, WWF Brazil, WWF USA, the Cargill Foundation, the World Bank/GEF, IDB, BNDES, Anglo American, Bahia Mineração, BP Brazil, FAO/GEF, Petrobras, and OGX.

The controversy surrounding donations from the GBMF and other foundations, funds, and companies stems from the fact that some of these funders have conflicting interests that could pose significant threats to the Amazon. For instance, Cargill—due to soybean cultivation in illegally deforested areas—and Petrobras, which has sought to explore oil and gas in the biome.

A report accessed by CENARIUM in June 2023 details the funding provided to Funbio. Among the donors is Anglo American, which contributed nearly R$ 19 million. The company describes itself as “a global diversified mining company with the purpose of reimagining mining to improve people’s lives.” Mining is considered one of the biggest environmental violators in the Amazon.

Another institution that provided millions in funding to Funbio, according to financial statements, was the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF), which focuses its donations in Brazil on one area: land, terrestrial ecosystems, and land use. The “strategies” for protected areas and Indigenous territories include conservation, consolidation, management, and monitoring.

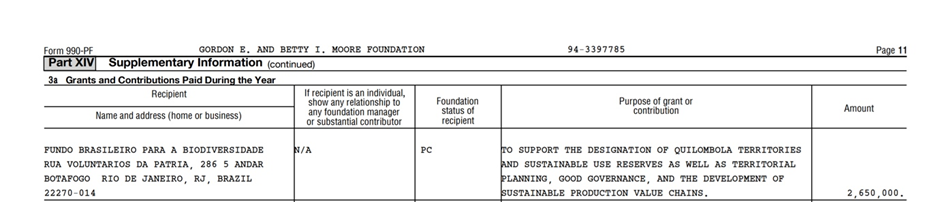

One of the documents shows contributions of R$ 15 million ($2.6 million) and R$ 6.9 million ($1.2 million), totaling R$ 21.9 million ($3.8 million), to “support the designation of quilombola territories and sustainable-use reserves, as well as territorial planning, good governance, and the development of sustainable value chains.”

Other documents indicate the allocation of R$ 3.7 million ($650,000) to “support collaboration between the Brazilian Biodiversity Fund and the federal agency for protected areas to create and implement tools and processes to unlock federal compensation funds for Amazon protected areas as part of the Arpa for Life initiative.” Additionally, R$ 867,000 ($150,000) was earmarked to “support a strategic plan for conservation financing.”

The highway and its history of controversies

The BR-319 was built to connect the state of Amazonas to the state of Rondônia during the military regime. Construction on the highway began in 1968, it was inaugurated in 1976, and definitively closed to continuous traffic in 1988. Its passable sections are located at the ends near Manaus (AM) and Porto Velho (RO).

The “Middle Section,” between kilometers 250 and 655, has been the subject of political and business discussions for decades regarding its repaving. The highway passes through the municipalities of Borba, Beruri, Manicoré, Tapauá, Canutama, and Humaitá, all in Amazonas.

The road was only passable for 12 years due to abandonment caused by the economic infeasibility of transportation compared to other modes, such as barge transport via the Madeira River.

In 2015, a new process to reactivate the land route and initiate a new maintenance license led to increased deforestation and land speculation in the region, along with complications in the licensing process. These included an attempt by the National Department of Transport Infrastructure (Dnit) to repave the road without proper environmental studies, without consulting affected traditional communities, and without an economic feasibility study, as noted in a preliminary injunction issued at the time by the Federal Court and researchers interviewed by CENARIUM.

Since the road’s continuous closure in 1988, new works only began on some sections in 2001. In 2005, a new debate emerged about repaving and reconstructing the entire stretch, but it was blocked by the Federal Court, which required Environmental Impact Studies (EIA) before continuing the works.

There were successive attempts to resume work, including in 2021. However, the environmental studies presented by Dnit that year were incomplete and inadequate, as indicated in a technical report by William Magnusson, a researcher at the National Institute for Amazonian Research (Inpa), requested by Federal Prosecutor Rafael Rocha.

Last year, a study published by researchers from the Federal University of Amazonas (Ufam) and Inpa, Lucas Ferrante and Philip Fearnside, respectively, pointed out that the public hearings on the environmental studies presented by Dnit in 2021 did not include the participation of affected traditional communities, marking the process as illegal.

After political pressure from Northern parliamentary groups, the federal government established the BR-319 Working Group (GT), which brought together various agencies to present suggestions and solutions. The group’s work resulted in a report released by the Ministry of Transport (MT) in June 2024, which concluded that repaving the highway was feasible and outlined certain measures to meet the social and environmental conditions required for license approval.

Researcher Lucas Ferrante warned in an interview that the agency does not have the authority to certify the project’s feasibility. “First and foremost, it is crucial to emphasize that the agency responsible for assessing the feasibility and sustainability of the highway is Ibama, not Dnit or the Ministry of Infrastructure. The report in question has the same validity as a note scribbled on a napkin—in other words, none. That is why it is essential to highlight that this document is highly biased,” he states.

“When analyzing this report, it is evident that all peer-reviewed scientific studies were excluded—a serious omission, especially since the GT formally requested these studies from me. It is worth noting that Brazilian law classifies the suppression of scientific information or technical data in environmental licensing processes as a crime. Therefore, what we are witnessing here is a violation committed by the GT technicians, who deliberately ignored scientific studies to construct a false narrative of the highway’s feasibility,” Ferrante adds.

Charlie Lot

In the media and in the Federal Congress, discussions about the reconstruction of the highway’s “Middle Section” are common. However, a 52-kilometer stretch of the highway known as “Lot C” or “Charlie Lot,“, or Charlie/C section, between kilometer 198 and kilometer 250, is also a cause for concern, as it lacks the required Environmental Impact Study (EIA) for its reconstruction project. The EIA for the BR-319 reconstruction project only covers the highway’s “Middle Section.“

The reconstruction of this section had been suspended by the Federal Court. However, on April 9, 2024, the Dnit issued an ordinance approving the “Basic Project” for the resurfacing of Lot C of the BR-319 Highway. Three months later, in July, the Federal Court of Amazonas once again suspended the preliminary license. The request was filed by the Climate Observatory.

The lawsuit pointed out that the license disregarded technical data, scientific analyses, and a series of reports prepared by Ibama itself throughout the environmental licensing process. Judge Mara Elisa Andrade, from the 7th Environmental and Agrarian Court of the Judiciary Section of Amazonas, ruled that environmental governance and deforestation control must be in place before the highway’s reconstruction.

However, in October of the same year, the Federal Regional Court of the 1st Region (TRF-1) overturned the injunction, allowing the preliminary license to proceed.

Suely Araújo, coordinator of the Climate Observatory and former president of the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), told CENARIUM that granting a preliminary license under the current conditions of the highway is not feasible.

“The Climate Observatory understands that, given the current conditions in the region, this road is unviable because it will greatly accelerate deforestation. That is the main concern. Technical reports indicate this, estimating that deforestation in the region could increase fourfold,” she stated.

Governance questioned

The study “Brazil’s Highway BR-319 demonstrates a crucial lack of environmental governance in Amazonia”, peer-reviewed and published by researchers Maryane Andrade, Lucas Ferrante, and Philip Fearnside in the scientific journal Environmental Conservation in 2021, pointed out that governance is absent in the BR-319 highway area and that institutions responsible for oversight, such as the National Institute for Colonisation and Agrarian Reform (Incra) and the Amazonas Institute for Environmental Protection (Ipaam), acted to legalise land grabbing and facilitate illegal deforestation.

Governance refers to the management and control of activities related to the maintenance, revitalisation, and use of a highway. In the case of BR-319, it involves a set of actions, including the federal government, state governments, environmental agencies, civil society organizations, and local communities, to ensure efficiency, sustainability, and accountability in the management of the highway.

For the coordinator of the Climate Observatory, Suely Araújo, who is a former president of the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), there is currently no environmental governance on BR-319, and isolated actions do not equate to governance.

“Well, the region does not have sufficient environmental governance to prevent the deforestation that this road will cause. In fact, the road will be rebuilt and paved—it is not just a simple paving, right? When you facilitate traffic on BR-319, you also facilitate deforestation. And in the region, there is not enough oversight to prevent this deforestation,” she states.

According to Suely, for governance to be effective, “public agencies need to work with structure and personnel. There must be an administrative organization guarantee that oversight will be in place. The pressure for deforestation that will be generated cannot be controlled with just two or three Ibama enforcement operations per year in the region. That is not enough,” she adds.

From the perspective of biologist and American scientist Phillip Fearnside, even with governance, BR-319 would still cause significant socio-environmental impacts. “Even if that were in place, the impacts would still be enormous. And the authorities do not have the capacity to control the situation,” he states.

“Unrealistic” scenarios

In the article titled “Environmental disaster in the Amazon and violation of Indigenous rights facilitated by governance projects on BR-319”, authored by Fearnside along with researcher Lucas Ferrante and journalist Monica Piccinini, the authors argue that “the BR-319 project has a long history of completely unrealistic ‘governance’ scenarios, including the first Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) claiming that the highway would resemble the roads of Yellowstone National Park, where millions of tourists drive without causing deforestation.”

Furthermore, according to the authors, members of the Federal Police and the Brazilian Army interviewed by them “made it clear that a future governance scenario is fictitious, as oversight bodies would not have the resources or personnel to monitor the area due to its size, complexity, and dangers.” Additionally, the article states that “organised crime already controls land grabbing and mining in the region, which has severely impacted traditional communities.”

CENARIUM requested statements from Incra and Ipaam regarding the study that pointed out partial actions by these agencies and also about their inspection structure for governance in the region. The report also sought contact with Ibama and the Federal Police to inquire about their inspection structure.

Ipaam stated in a note that its competence is focused on environmental licensing and supervision of activities that may have environmental impacts. The agency emphasized that BR-319 falls under federal jurisdiction, making it primarily the responsibility of federal environmental and land agencies. It also highlighted its main work on the highway through Operation Tamoiotatá, which carries out enforcement actions to combat illegal deforestation and other environmental impacts in the southern region of Amazonas. In 2024, this operation resulted in 187 infraction notices, totaling R$184 million in fines, and 349 embargo terms, covering 28,500 hectares of degraded areas.

Ipaam also informed that it carries out its activities in sensitive sections of BR-319, particularly in the middle stretch between the districts of Realidade and Castanho, as well as in regions of the municipalities of Humaitá, Canutama, Tapauá, Borba, among others.

There was no response from the other agencies by the time of publication.

Violations of rights and reports of pressure on Indigenous peoples

Currently, the National Department of Transport Infrastructure (Dnit) argues that it will only consult six Indigenous groups, a small number considering that there are 69 Indigenous groups affected by BR-319 (63 recognized Indigenous Territories, 5 unofficial ones, and one isolated group), where deforestation strips are three times larger. More than 18,000 Indigenous people are expected to be affected by the highway, according to researcher Lucas Ferrante, including isolated Indigenous peoples.

In addition to scientists’ warnings about the project that threatens the rights of traditional communities along BR-319, Indigenous people from the confluence region of the highway reported to CENARIUM violations of rights, threats, and the scarcity of essential life goods due to the deterioration of the territories caused by the road’s expansion. The information reached the report during the Seminar and Meeting Between Indigenous Leaders, Researchers, and Decision-Makers on the Impacts of the BR-319 Highway, held at the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM). The event, coordinated by researcher Dr. Lucas Ferrante from UFAM and the University of São Paulo (USP), brought together Indigenous people and decision-makers to discuss the impacts of the project.

On that occasion, the group presented a document produced by the International Institute of Education of Brazil (IEB), which stated that the Indigenous people of Lago Capanã Grande and Baetas had been consulted about BR-319 and agreed to the paving of the highway on the condition that an extractive reserve be created to protect them.

However, the Indigenous people state that they disagree with the document’s content.

“We, the Mura people from Lago Capanã and Baetas, agreed to the paving works of BR-319 as long as the protection of our chestnut tree areas was ensured through the creation of a Resex for our exclusive use as part of the environmental compensation for that project. However, these very areas are being invaded, illegally appropriated, and deforested. Large markings are being made to divide our area of use, and a pathway is being opened to reach the Madeira River from BR-319. If there is no forest and chestnut tree area left, we Mura can no longer agree to the construction of BR-319 because the impacts would be too great for us in the Mura communities of Lago Capanã and Baetas, who live in small and fragmented lands,” stated an excerpt from the document.

“We do not agree, and we had not read this document,” said an Indigenous leader from Lago Capanã in a video, who requested anonymity for fear of threats. With the document in hand, he said he received it from an IEB employee named Carlos. The Indigenous people believed it to be a report on deforestation in the region.

According to the Indigenous leader, the IEB employee instructed them to deliver the document to the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) and the National Department of Transport Infrastructure (Dnit). For the group, the IEB document was an attempt to circumvent Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO).

The Federal Public Prossecutor’s Office (MPF) is aware that the agencies responsible for the BR-319 project are, according to reports, violating the rights of traditional peoples, such as riverside dwellers, extractivists, babassu nut breakers, and quilombolas, by failing to conduct consultations, as confirmed to the report in June 2024 by Republic Prosecutor Janaína Mascarenhas, responsible for cases related to the highway within the agency. Previously, the responsible prosecutor was Fernando Merloto.

“All Indigenous peoples and traditional communities have the right to this consultation before any project that could impact their lives. This consultation has never been conducted in the case of BR-319 with any Indigenous people or traditional community. This is even known to the federal government itself,” declared the prosecutor.

A demarcated Indigenous Territory is the main demand of these peoples. This is because, if homologated, the territory is constitutionally protected under the 1988 Federal Constitution, which guarantees Indigenous peoples the right to permanent possession and exclusive use of the soil, rivers, and lakes’ resources within their lands. This right is recognized as original, meaning it predates the very formation of the Brazilian state.

Destruction

In another video, the chief of one of the villages on the banks of Lago Capanã Grande, who also requested anonymity, told the report that the local peoples are in mourning and are concerned about the fate of the communities with the progress of the BR-319 project. He states that, contrary to what is reported in the media, the highway will bring no benefits to Indigenous people and that the impacts are already being felt. The video was recorded by CENARIUM.

“Today, Capanã is in mourning,” he said. “Our territory is being severely degraded, with many chestnut trees destroyed. Today, we are suffering with our fish, our game, our waters, and our igarapé springs, which are all being buried by land grabbers. The population is also suffering a lot from diarrhea, fever, and vomiting. These issues have increased, you understand?”

According to reports, the destruction of chestnut groves resulted from deforestation advancing along the highway. Meanwhile, the diseases stem from contaminated waters due to territorial degradation. The lake is also drying up since the igarapés that feed Lago Capanã Grande are being buried by the construction of illegal roads, including by Dnit itself, responsible for the highway project.

“The chestnut groves we had, from which we used to harvest fruit to buy our food, are practically all gone. There are 16 chestnut groves that have been entirely destroyed. There are open fields where we can’t even see the end. So, BR-319 will never bring us a future—it’s always a loss,” another Indigenous person said in a video, adding that everyone lives in constant fear of threats from invaders.

North American biologist and scientist Phillip Fearnside highlighted that he was shocked by the stance of NGOs supporting the paving of BR-319. “What was striking was that not only FGV but also other NGOs were not condemning the construction of the highway; they were advocating for governance, allowing the project to proceed. And I made a presentation at the MPF, showing that there are enormous impacts, that it really should not be approved. Since then, we have conducted several studies, and there are multiple publications demonstrating this,” he recalled.

The other side

To CENARIUM, the MPF confirmed that Prosecutor Fernando Merloto is no longer handling the case. The agency stated that it is “working on the necessary legal measures to guarantee the consultation rights of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities.”

In clarification, the IEB stated that its position is the defense of Indigenous peoples’ and traditional communities’ rights, regardless of the repaving of BR-319, and confirmed that it has been operating in the region since 2020, “supporting the construction of consultation and consent protocols for affected Indigenous peoples and traditional communities due to the highway’s repaving and other large-scale socio-environmental impact projects.”

The report questioned the role of an employee named “Carlos” around BR-319, who was mentioned by Indigenous people as the person who provided them with a document encouraging a favorable position on BR-319, and is awaiting a response.

In response to the report, WWF-Brasil stated that it does not have an active partnership with the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation in its projects. Regarding corporate relationships, the organization said it seeks “transformational partnerships that change company practices and their supply chains, thus influencing the sector in which they operate,” acting “based on transparency, with reports and accounts audited annually by some of the world’s most recognized auditing firms.”

Idesam informed that it will not comment on the matter.

Other Responses

CENARIUM also sent requests for statements to FGV and GBMF, questioning whether the transfer and/or receipt of funds does not constitute a conflict of interest. A request was also sent to Eneva regarding the company’s relationship with Dynamo and GBMF. As of the closing of this edition, there has been no response.